(The following is a short summary. A more in-depth report of the project will soon be supplied in pdf. For audio examples please visit “The Diagram” and “Rhizomatic Scores” sections under the “Results” menu tab)

All artistic productions — audio & video recordings, visual maps and images, etc., encountered in the Activities — are to be considered as results in themselves, thus constituting a domain of materiality that embodies the experiences and insights of our research process alongside the discursive domain of written texts. We do not regard these domains as simply complementary but wish to emphasize the ways in which they may both resonate and interfere with each other. The domain of materiality has something to say on its own, a performative force that may effect movements in thought in ways that we have not ourselves envisioned.

In a somewhat similar sense, the project’s process, as documented in the Activities, is important in its own way. This is so because at every twist and turn there are other possibilities still awaiting potential development, and these possibilities could become at least as relevant or interesting as the ones we have chosen to pursue here. Because the project has been about progressively comprehending the problems of collective improvisation — the problem of heterogeneity for example — it is more about opening a space for many possible solutions. In our view, learning by doing — through the intertwining of materials, concepts, models, and so on — entails progressively discerning what is or could be relevant, and this can only unfold in and through an open-ended series of experiments that between each other say something, taken together as it were.

Using process philosophy, we could say that a problem has an autonomous existence as a virtual entity and as such it continues to exist even after actual solutions are found. This means that what is “problematic” is not in need of an explanation, in the sense of a solution that dissolves the problem. Rather, as philosopher Manuel DeLanda puts it, problems are problems of the world (instead of simply “mental” or “logical” problems) that continue to exist – or “insist” – independently of its particular solutions. The perhaps clearest example of such virtual entities are possibility spaces in physics: “The simplest possibility space, one structured by a single minimum or maximum, defines an objective optimisation problem, a problem that a variety of actual entities (bubbles, crystals, light rays) must solve in different ways. But the optimisation problem survives its solutions, ready to be confronted again when a flat piece of soap film must wrap itself into a sphere; or a set of atoms must conform itself to the polyhedral shape of a crystal; or a light ray must discover the quickest path between two points” (DeLanda 2016: 178). In this perspective, the only thing we could ever really hope to accomplish with our project is to comprehend something of the complexity of collective improvisation in terms of a set of autonomous and generative virtual problems that can only be hinted at, and which continue to insist beyond our particular solutions. The Diagram below is one result of this ambition.

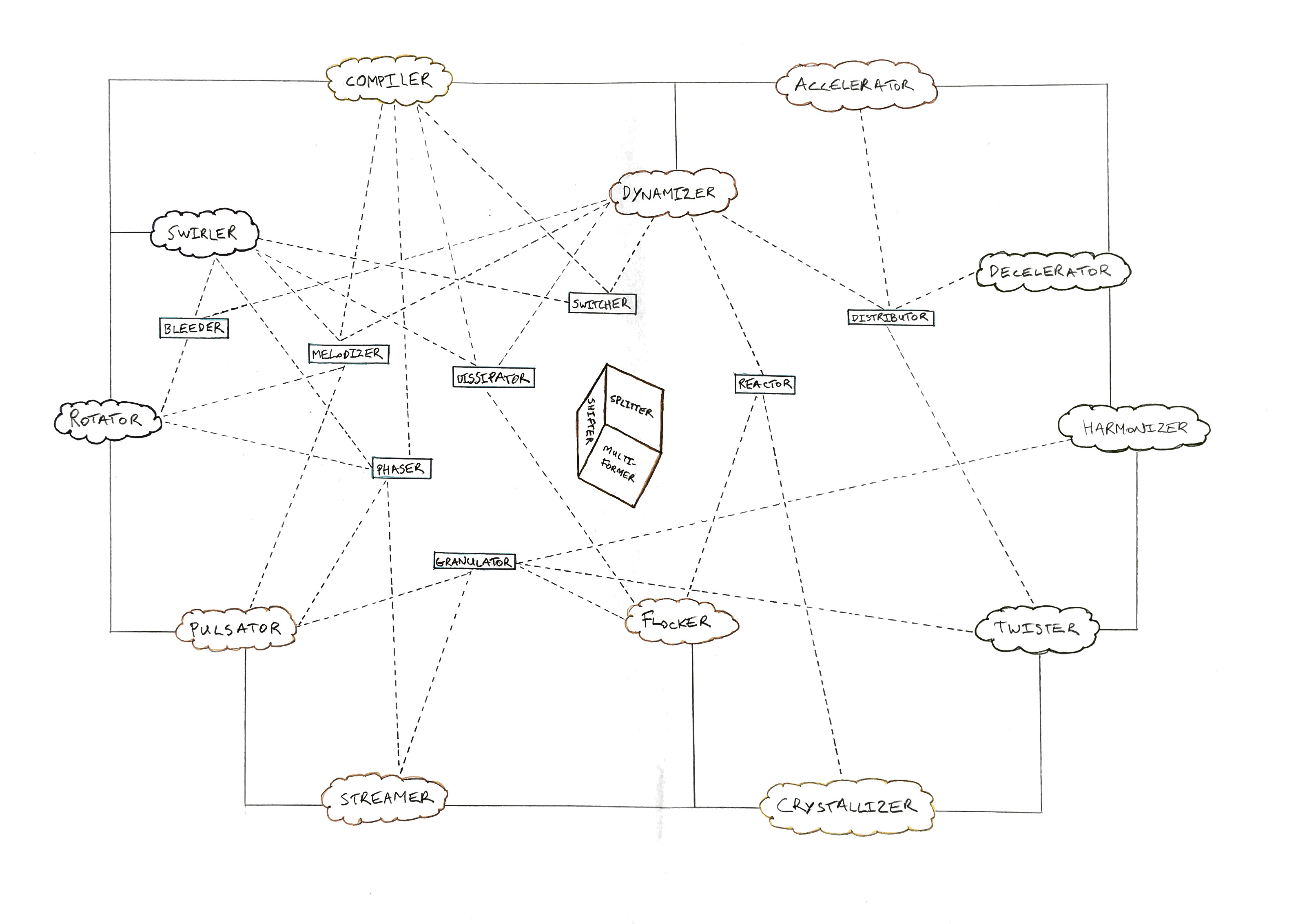

The Diagram assembles this project’s intertwined concepts and methods in a map that forms a dynamic system of forces cutting across the various terrains of conceptual and practical domains. This map is a visualization of our concept-methods and their connections, presenting them in a format that can set things in motion. As such it offers a meta-modelization of the project’s processes.

The Diagram has been constructed through a transversal criss-crossing between intuiting systemic behaviours of our collective improvisations, intermingling these intuitions with a variety of concepts, designing new concepts and methods, and conducting a series of experiments based on these. This procedure has been repeated many times over, ultimately resulting in the selection of Attractors, Resonators and Connectors that constitute the Diagram in its current form.

The Diagram should be regarded as a possibility space: a virtual potentiality with implicit tendencies toward unfolding new possibilities, directed towards an open future beyond its present form. This open-endedness is not simply trivial, in the sense that things can always be “improved” or “develop further”, but rather in the sense that the significance of the Diagram resides precisely in its calling for a future. Understanding the Diagram as a form of “finalization” (however temporary) would therefore compromise its significance. Although the Diagram does say something about our ways of improvising — how these have changed and could continue to change — it does so only on a level of abstraction that challenges us (or anyone) to conduct further experiments. Put differently, the Diagram is not a representation of the past, nor is it a prediction, but an implicit future that can only come to expression by doing something: whether using it for an experimentation with collective improvisation or for catalyzing creative thought in connection with other domains.

The primary components in the Diagram are what we call Attractors (the cloud-like figures). Each Attractor combines certain parameters for improvisation (or Modulators — see “Jun. 14, 2018” in Activities) in a way that, taken together, invite for collective behaviour. But they do this by offering a relatively large spectrum for nonlinear complexity. Attractors thus function through what we call quasi-causal constraints, which means that they do not directly control improvisation (as “ideals” would) but more indirectly construct an abstract space within which a variation of choices and/or interactions may occur. As such, an Attractor attracts the improvisation in more or less unpredictable directions.

From one perspective, Attractors are like systemic behaviours that may arise without necessarily relying on conscious intentions or choices, expressing the tendencies and constraints that we deal with in our collective improvisations. But Attractors may also, simultaneously, serve as a genetic material to afford new possibilities, like flexible tools that can be intentionally applied in and through ways of thinking and acting. Their abstract space then afford opportunities for playfully exploring limits and potentials among many lines of continuous variation, as well as offering opportunities for qualitative transformation of collective behaviour.

Attractors could be understood in terms of an affective attunement (as psychiatrist Daniel Stern calls it), one which “finds difference in unison, and concertation in difference” (Brian Massumi 2015: 56). When there is a collective event — as “bodies indexed to the same cut, primed to the same cue, shocked in concert” — it is “distributed across those bodies. Since each body will carry a different set of tendencies and capacities, there is no guarantee that they will act in unison even if they are cued in concert. However different their eventual actions, all will have unfolded from the same suspense. They will have been attuned — differentially — to the same interruptive commotion” (Massumi 2015: 55-6).

All Attractors involve a high degree of morphability and variation, as well as a permeability for being juxtaposed, amalgamated or superimposed with each other. For example, small variations will sometimes imply radically different results, and Attractors could also be combined, simultaneously pulling at each other as “coexisting centers of gravity” (Rosenberg 2010: 208). Sometimes there is a zone of indiscernibility in which an Attractor overlaps with other Attractors (some of these zones are indicated by the placement of Attractors in the Diagram), at other times there may be thresholds at which one Attractor qualitatively turns into another Attractor. Or, within a zone of sensitivity, minimal fluctuations could push the collective improvisation towards an entirely different pattern.

To the extent that collective improvisation involves nonlinear events, collective behaviours could thus happen in ways that are shaped by the Attractor associated with it, but they could also suddenly move away from that Attractor and do something else entirely, or they could map onto a different Attractor. This is so because positive feedback mechanisms — reciprocal interaction, or “resonance” — between musicians, or musicians and machines, can set up runaway growth or decline, so the qualitative changes affected by Attractors are typically unpredictable and multi-faceted. This nonlinearity could be understood in terms of what in turbulent or chaotic systems are called “strange” or “fractal” attractors. This means that to the extent that collective improvisation exhibits extremely sensitive dependence on how things change this makes it highly unstable, yet certain thresholds and sensitive zones can be revisited without ever being fully replicated in their exact details.

What is artistically relevant is how we as improvisers are challenged by the “resistance” or “attraction” of Attractors. The most important point, then, is that an Attractor is not in any way an ideal, but rather that it can engage improvisers differentially to some extent. So even if Attractors afford an insight into our artistic practice they are not always useful for identifying what happens / has happened in a particular improvisation because an Attractor need not be clearly perceived by an external listener. Improvisations influenced by an Attractor need not take a particular form, because although the Attractors attract behaviours by moving them towards qualitative thresholds they will typically do so in unpredictable ways.

Attractors have a level of abstraction that focuses on the flexible variation of, and connectivity between, the “Modulators” (parameters for improvisation – such as ideas, materials, relations, responses, roles, listening modes, and rate, range or direction of change). This entails that one can only experiment with how an Attractor’s components may interact in various ways, as well as how this may involve critical thresholds or sensitive zones by which improvisation may produce plateaus of intensification. An important challenge in the project has been to decode and deterritorialize our improvisations and experiments to reach the more abstract Attractors. Put differently, constructing Attractors has involved eliminating as many of the details of an actual improvisation event as possible except what can be called its “topological invariants” — that is to say, the virtual structures of the Attractor that tend to constrain processes independently of actual mechanisms. To return to the previous example, “the mechanism which leads to the production of a soap bubble is quite different from the one leading to a salt crystal, yet both are minimizing processes” (DeLanda 2002: 15), and it is precisely this mechanism-independence that makes Attractors so useful.

Whereas ideals (a pre-existing form which remains the same for all time) make us think about particular improvisations as mere copies, thus resembling the ideal with a higher or lower degree of perfection, Attractors require instead that we think about difference positively or productively, as that which drives a dynamical process. And it is precisely the Modulators’ differences — their constant “internal variation”, as well as the ways they reciprocally affect each other in positive feedback mechanisms — that constitute the inherently dynamic morphogenetic processes involved in Attractors.

This means that Attractors cannot be understood by defining them in terms of a set of essential characteristics or fundamental traits that would explain their identity. This would reduce the role of analysis to a purely logical process, and such an Attractor would be basically static and timeless (like an eternal archetype). In our research we have not been interested in such logical-conceptual analysis, but have rather been conducting causal interventions in improvisation and observing their effects in an attempt to explore variations of materials, strategies, and so on. This has then been combined with a kind of “quasi-causal analysis”, an intermingling of intuitions and conceptualizations that would reveal the constraints that structure an Attractor’s possibility space. This causal and quasi-causal work cannot be said to have simply uncovered a “pre-existent” virtual structure. Rather, the virtual structures have been partly constructed in and through the research process, and they also continue to change with further experiments.

In summary, Attractors could be said to insist within spectrums of connectivity, as obscure distinctions within many criss-crossing continuums of variation. This entails that they will always “play out” or sound in many different ways, not least in ways that participating improvisers cannot fully control. Moreover, working with the Diagram in cycles of intuition, conceptualization and experimentation will continuously restructure the Attractors in and through the way they are intuitionally grasped. All this entails that Attractors can hardly be said to function as idiomatic models in a traditional sense, although they do express a certain ethos: a nomadic ethico-politics that emphasizes heterogeneity, change and difference.

The Resonators (boxes in the Diagram) consist of a smaller selection of Modulators, and their functionality depends precisely on their simplicity. Resonators too are multifunctional. For example, a Resonator could be used to create resonances and interferences between Attractors by affording mixtures or transitions between them; or it could work by itself (thus becoming more Attractor-like); or it could be used to modulate an Attractor. Resonators may thus afford any of the following: entries into Attractors (as heightened opportunities for sync points or “emergence”); exits away from them (as “lines of flight” or “loopholes”); inflections, morphings and tweakings; Attractor-like resources for improvisational material; as well as transversal passages and connections of any kind.

The dashed lines between Resonators and Attractors indicate particularly accessible resonances due to the nature of overlap between them. For example, “Phaser” involves phasing in and out of sync in rhythmic relations, which naturally connects with certain Attractors. As such, it affords opportunities not only for modulating those Attractors but also for transitioning or morphing between them. In our experience, connections that explicitly invite for certain opportunities are beneficial in a mapping of tendencies so that they can be affirmed as well as actively diverged from. However, any Resonator could of course be used at any time, or in connection with any Attractor.

Despite their simplicity, Resonators too are exploratory, similarly to Attractors: they consist of a continuum of variation, not only in terms of the explicit components that compose its focus, but precisely in their ability to be used in connection with a large variety of Modulators.

Finally, Connectors (the cube in the center) afford possibilities for variation in larger structures of form. They do not, however, do this through a top-down approach, by which a particular architectural design would be imposed on the content of improvisation. Rather, they do this in a bottom-up fashion by engaging immanent procedures in the form of direct connections and dis-connections, so that an unpredictable variety of larger forms may emerge.

The Diagram is also a programme of transformation — an experimental pragmatics that involves micro-political aspects — because it not only enables things to happen in musical improvisation but may simultaneously involve the transformation of the subjectivity of musicians and listeners, as well as differently engage relations between human and non-human forces.

We could also approach the Diagram in terms of what Deleuze and Guattari (2004: 142) called an abstract machine: “The diagrammatic or abstract machine does not function to represent, even something real, but rather constructs a real that is yet to come, a new type of reality”. The abstract machine thus relates to the future orientation — or diagrammatic function — of experimental art (O’Sullivan 2010: 205). The concept-methods included in the Diagram informs criteria for experimentation and as such they could connect with other extra-musical experimentations, creating new intensities in those situations and allowing for previously unavailable possibilities. Put differently, an abstract machine could become operative in different fields or domains, in other assemblages with other components, to the extent that they exhibit isomorphic processes. In this view, abstract machines “are not mere metaphors: they are engines or devices that both capture and process forces and energies, facilitating interrelations, multiple connections, and assemblages” (Braidotti 2011: 62).

Abstract machines can lead to constructive experiments that liberate us from conventions, habits or routines that have blocked other possibilities of action and thinking. In an experimental pragmatics, the always important challenge is how to remove such blockages, in and through an abstract machine of mutation. It is perhaps the transfer of the force of an abstract machine into a different practice or field that especially enables something new to happen, restructuring assemblages in that other field (as well as restructuring the abstract machine itself in light of this encounter). The transferability of abstract machines between domains would then depend on their level of abstraction.

The Diagram could, then, be used to construct abstract machines of mutation by further abstracting the Attractors in ways that make them less explicitly connected to a musical context. This would then be a matter of practical experimentation rather than a purely conceptual work. Such experimentation would transform the concept-methods in the Diagram in and through encounters with other fields. Within the research project we have conducted some preliminary experiments with improvising dancers to explore the potential for the Diagram to engage such abstract machines of mutation for collective creativity in other fields.

______

Braidotti, Rosi 2011. Nomadic Theory: The Portable Rosi Braidotti. New York: Columbia University Press.

DeLanda, Manuel 2016. Assemblage Theory. Edinburgh Univ. Press.

DeLanda, Manuel 2002. Intensive Science and Virtual Philosophy. London & New York: Continuum.

Deleuze, Gilles and Felix Guattari 2004. A Thousand Plateaus, London and New York: Continuum. (Trans. B. Massumi.)

Massumi, Brian 2015. Politics of Affect, Polity Press.

O’Sullivan, Simon 2010. ‘From Aesthetics to the Abstract Machine: Deleuze, Guattari and Contemporary Art Practice’, Deleuze and Contemporary Art, Edinburgh University Press, pp. 189-207.